The Installation Lap is a weekly Substack column dedicated to helping Americans develop a deeper appreciation for Formula 1.

When I began to immerse myself in the thrilling universe of Formula 1, I quickly found myself puzzled as to the exclusivity of those 20 drivers on the grid who are the only ones in the world “allowed” to drive these amazing cars. With a vast array of motor racing categories in existence, it seemed preposterous to assert that these 20 were the only people capable of expertly manipulating the gas, brake, and steering wheel of these amazing machines. But as my understanding of the sport slowly deepened, I came to see that Formula 1 isn’t about mere speed but the drivers’ capacity to be continually fast in a multitude of constantly shifting situations. It’s their ability to interpret, adapt, and push beyond that are the hoof prints of F1 exceptionalism.

While modern F1 drivers shoulder a whole host of responsibilities that even many of their most lauded predecessors never had to contend with, it is these drivers’ ability to get up to speed quickly, be fast consistently, and cease on every single opportunity and risk possible along the way without stepping over the edge that separates them from their talented colleagues in other racing categories. One of the clearest ways we can see this talent made manifest is in how F1 drivers go about driving around a lap. What lines do they take, and why?

It may seem reductive, but in a general sense, F1 drivers are doing exactly what other elite drivers are doing when they navigate a corner, just more so. This is essentially the defining ethos of Formula 1. We’ve touched on this in previous columns, but at its core, everything in F1 is dialed up to the nth degree. How drivers choose and negotiate, turns is the same.

The absolute fastest way through any corner is to take what’s called the geometric line. The geometric line represents the shortest distance between two points, the corner entry, and the corner exit. The wrinkle comes into play when you zoom out to see that a race track is a series of interconnected corners. Thus, taking the perfect geometric line through one corner could result in a car being out of position for the following corner, which would then slow your momentum as you try to make adjustments to navigate that second corner. An example of this basic concept is the first two turns at the Baku circuit in Azerbaijan. Turns 1 and 2 there are both 90º corners. You’ve got the longest straight in F1 leading into the first turn, so taking the geometric apex here is, in general, the fastest way through. Taking this line will have you set up perfectly to take turn 2. But here’s the catch, while turn 2 is just another simple 90º turn, immediately following turn two is a medium-sized straight with a DRS zone. While one could take the geometric apex through turn 2, doing so could well compromise your top speed on the straight, leaving you vulnerable to the driver right behind you who has taken a late apex. Taking a late apex here allows the following driver to get the car pointing straight - faster, allowing them to get on the throttle faster and thus carry more speed down the straight. When I say “faster” here, I am talking about milliseconds. Turning the car and getting on the throttle just that little bit sooner can result in a speed difference at the other end of the straight which could mean the difference between making a pass or having to sit behind for one more lap. F1 drivers are making these kinds of decisions constantly, at eye-watering speeds.

In the simplest terms, racing drivers are trying to maximize their speed through all phases of a given corner (as seen here in one of the greatest laps ever driven). The essence of this desire to maximize speed is distilled into four corner phases: braking, turn-in, apex, and exit. Each requires an intricate level of understanding and expertise that distinguishes the best from the rest. When Formula 1 drivers navigate these phases, they’re pushing the boundaries of speed, adhesion, and courage. Mastering these four phases is the work of “normal” racing drivers. Pushing these four phases to the absolute limit is what Formula 1 drivers do.

Braking, for instance, is not just about slowing the car down, but doing so at the right time, in the right way. Elite drivers such as Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen have demonstrated an otherworldly ability to handle the brakes with consistent precision, turning this phase into an art form.

The turn-in phase requires subtlety and finesse as drivers strive to maintain control and momentum. Turn-in is the exact moment the driver turns the steering wheel and aims the car toward the apex. The primary goal here is to turn the wheel as smoothly as possible. Once the steering wheel beings to turn, the weight of the car is going to shift. Rob Wilson, an esteemed driving coach, offers a novel perspective on this with his “flat car” theory. Wilson’s concept states that a car will always be going its fastest in a straight line. Whenever you’re turning, you’re scrubbing speed. Wilson’s insight here is instead of driving a single smooth line through a turn, the driver should break that turn into smaller straights and work to keep the platform of the car flat. For Wilson, this incremental loading of weight and forces on the car is the way to go fast. Wilson has repeatedly praised Kimi Raikkonen for his ability to do this.

At the apex, the goal is twofold: touch the apex and get on the throttle at the earliest possible moment, thus maximizing our exit speed. Mastering this phase can be a game changer, notes Scott Mansel of Driver 61 fame. Mansel explains that a common mistake amateur drivers will make in this area is that they are too aggressive in applying the brakes and too aggressive in getting on the throttle. Elite drivers, says Mansel, will coast through the apex and then pick up the throttle at the earliest possible moment. The exit phase, however, is where drives such as Max Verstappen truly shine. Exiting the corner optimally sets the speed for the next section of the track, and if overdone by, say, getting on the throttle too hard, can lead to sliding, or worse.

These drivers also excel in learning and adapting to tracks faster than their peers in other racing categories. The ability to swiftly understand the nuances of a track and deliver high-speed laps soon after arrival distinguishes them. Their fast learning translates into faster driving.

Renowned Formula 1 journalist Peter Windsor highlights another dimension of the drivers' prowess, their ability to 'shorten corners.' Fans of TIL know of our admiration for Peter Windsor, and in deep explorations of F1 drivers and the subtle but important differences in their driving styles, Peter is forever highlighting that the very best F1 drivers (Lewis, Max, Charles, et al.) have a way of shortening the length of corners that others simply cannot match. In simple terms, these elite drivers are traversing less distance around a circuit than many of their competitors. They are accomplishing this by shaving every possible millimeter off of every corner they encounter. This takes both tremendous skill and bravery. Max Verstappen’s third sector in this year’s Monaco Gp qualifying beautifully illustrates this concept. Max made up over a tenth of a second deficit to Fernando Alonso on a single corner because he was able to shave that corner and carry more speed than Fernando Alonso. I’ve recently been mesmerized by the gorgeous and deeply informative videos made by Formula Addict on YouTube when it comes to scrutinizing racing lines, these 3D-rendered lap comparisons are a great way to see this corner-shortening ability Windsor refers to. This is the difference between good and great, even at the highest level of motorsport.

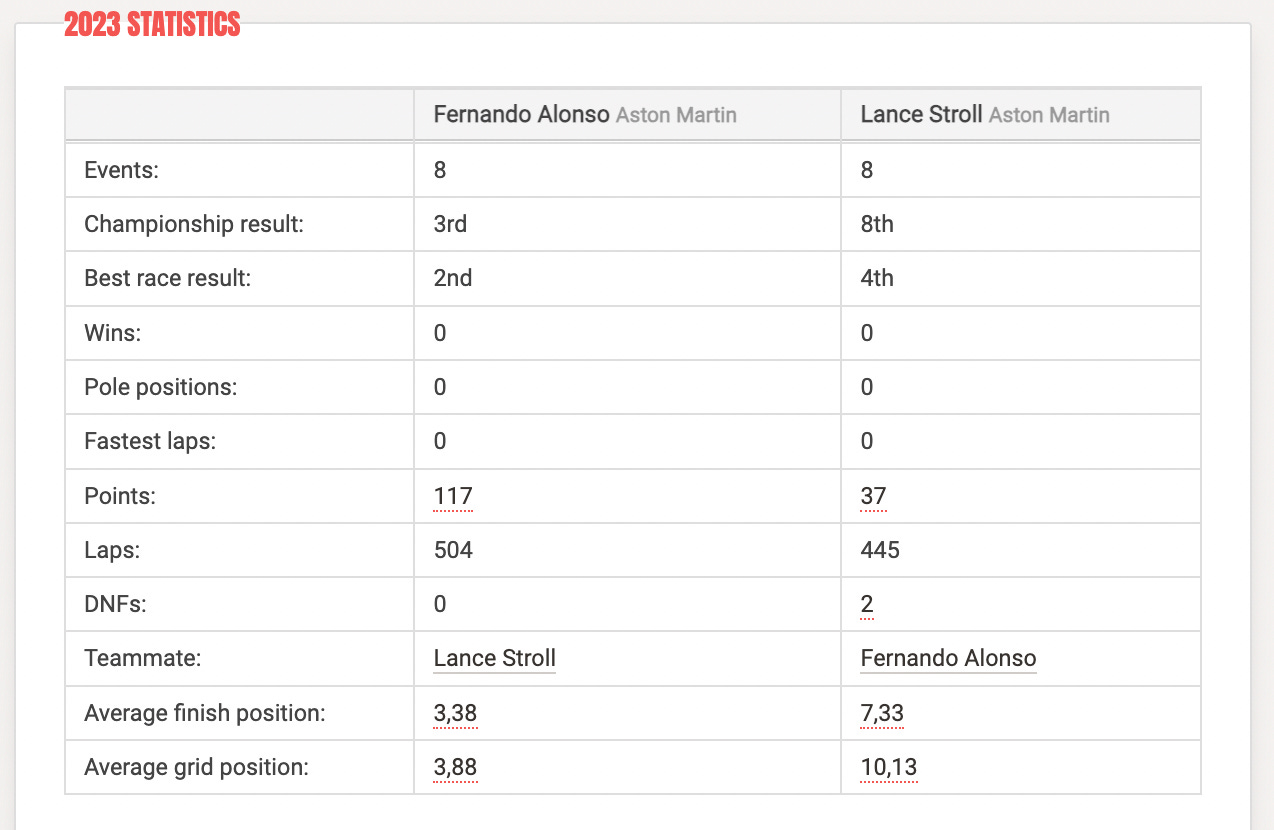

Taken all together, it gives the impression that drivers have a lot on their minds, they do, and driving is just a small part of it. What is so interesting about F1 is that drivers are making these decisions and navigating these corners in a strange liminal mental space, somewhere between the conscious and unconscious. Drivers are asked to not only drive the car as quickly as possible, navigating turns as we’ve discussed, but they are also simultaneously racing one another, which often takes them off of their preferred racing lines, making countless adjustments to their cars’ performance via the steering wheel, they are communicating with their teams on the radio, and they are trying to peer into the future of a given race looking for opportunities to over-cut or under-cut their opponents on race strategy while they manage their tires and brake temperatures. Add into that the fact that drivers are also responsible for being aware of the different lights, flags, and signals coming at them meant to ensure fair racing and safety. Modern F1 drivers are under massive cognitive stress at any given moment. It is from this cluttered psychosphere that we see true greatness emerge. Martin Brundle, former F1 driver and current F1 commentator, has said of Fernando Alonso that he uses 25% of his brain to actually drive the car and the rest for race strategy and planning. It is this cognitive ability, coupled with the physical and sensorial talents a driver brings to the table, that makes all the difference on a Sunday afternoon. This year we are watching on as Max Verstappen buries his teammate Sergio Perez. Lewis is edging out George, who is showing himself to be a genuine star, and Fernando Alonso is absolutely demolishing the boss’s son. It has been a true pleasure to watch as the likes of these three - two of whom are the oldest drivers on the grid, consistently demonstrate what makes them all-time greats. When this era is over, I think we will all count ourselves lucky to have witnessed the kind of excellence we are seeing at the sharp end of the grid this year.